Retro-Computing

A hodgepodge of posts that are all about old computers and technology like Apple ][ and Atari and vintage gaming platforms.

A hodgepodge of posts that are all about old computers and technology like Apple ][ and Atari and vintage gaming platforms.

As with most of the great shareware titles of the 90s, I played the free episode of Wolfenstein 3D a gazillion times but never bothered to buy the complete package. Once again with thanks to GOG.com I have been able to finally complete in its entirety. This is the progenitor of first-person shooters and the basic game mechanics are still pretty solid. Its main problem is that of repetitiveness. There are only four kinds of enemies to fight. That isn’t including the bosses at the end of every episode which all have a unique sprite and some even have an elaborate death sequence:

But even those bosses all kinda fight in the same manner.

Levels are built on a grid of right angles so that most can be navigated by simply always going to the right. There are no realistic shadows or lighting. The overall effect is that of being in a sterile, strip-mall dentist’s office. Playing this again really made me appreciate the giant step forward that Doom was. Despite these complaints, blasting away Nazi’s is still fun.

As you can probably see in my screen grabs, I was using a mod that gave me a minimap and also, more importantly, mapped the controls to the modern WASD layout. The map does break the game a little in that it eliminates the need to hunting for secrets. Having to push every wall randomly was never really a great design choice anyways.

I think this is considered by many to be one of the best point and click adventure games of the early nineties. I can see why people remember it fondly. The cyberpunk setting is unique (if you don’t count Neuromancer or just about every CD-ROM title from the same era), the production is impressive, and the game is massive for a point and click. At the time of this writing it is still offered as a free game on GOG.com. Unfortunately, I felt it to be a bit too oblique and meandering. I found the puzzles frustrating and I eventually gave up, finishing the game with a walk-through. Even with explicit instructions, I had no idea why I had to complete tasks. All I know is that I had to get to the ground floor of the tower. Somewhere in there was a story about discovering my past but that kinda gets lost when you are scrounging for dog treats so you can lure an heiresses’s dog onto a plank in order to catapult it into a pond thereby distracting a guard so you can enter a church so you can… you get the picture.

In the 90s, I tried playing the demo of this game many times and could never really get into it. Crusader was one of the best looking PC games of its time and I really wanted to like it. But the controls. Oh my God, the controls. Eventually, this scheme would go on to be described as tank controls in other games like Resident Evil. Basically, you aim and move your character in relation to the direction their sprite is facing rather than the direction you want them to move on the screen. Crusader takes that counter-intuitive mechanic to a whole new level of complexity by adding jumping, diving and ducking to the mix.

There are some default mouse controls which almost work, but your character is stuck with gun drawn, shuffling around like a man with his pants around his ankles. I got about a third the way through the game doing that until just gave up and set the game aside for a while. Months later I returned and forced myself to learn the standard keyboard controls. These are still clunky, but with practice and a lot of help from the auto-aim feature the game becomes much more fast-paced and responsive. Even then, the mouse is still helpful when the occasional fast-spinning aiming is required. For the most part, it pays to just bite the bullet and learn the keyboard controls. Think of Crusader like Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing but with more explosions and incinerated humans.

Once the control hurdles are overcome, the game itself is a huge, detailed and fun action game. The dialogue makes it seem like you are some sort of stealth agent who quietly infiltrates bases. In actuality, you are beaming in and killing everything in site while causing as much destruction in your wake as you can. There is a bit of setting up and planning of your attacks, but that’s as far as Crusader goes in being a stealth game. Just kill the enemies and watch them explode, melt and burn in screams of agony.

What little plot is here comes in the form of live-action cut scenes that are just as cheesy as one would expect from a 90s action game. They don’t really rise to the level of camp I would have liked to see, so skipping past them is a wise option. For all the detail that is in the game’s stellar isometric art, you would have thought they could have devoted a little of that effort to the set design in the live-action scenes, eighty percent of which a filmed with characters sitting in a restaurant booth. Who’d of thought world-wide revolution would be schemed from within a Steak ‘n’ Shake?

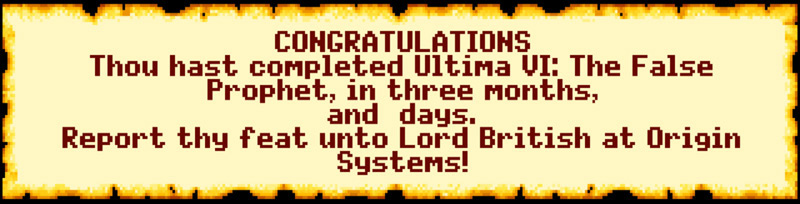

With the completion of VI, I’m getting close to having played all the games in the Ultima series. I own boxed copies of the Apple ][ versions of III–V, but when it came to VI, Origin switched to MS-DOS. In 1990 I was starting college, I didn’t own a computer, let alone a PC, and, as the years passed, history became legend, legend became myth, and for two-and-a-half thousand years, the Ultima series passed out of all knowledge… or something like that.

In the late 90s I upgraded from an Apple IIgs to a Windows 95 PC and was reintroduced to the series via a soundcard bundled version of Ultima VIII: Pagan. That game was mediocre at best and it didn’t finish it until years later—after having played through a CD-ROM Classics version of Ultima VII. VII was a pain to get running on a Windows machine, but it was worth it. It truly is the precursor to modern, open-world RPGs like Skyrim in both its scope and richness of detail.

The False Prophet almost achieves the level of refinement that Ultima VII boasts. It’s not quite there yet, retaining a bit of the Apple ][ era feel. Maybe that’s why I think I liked this a bit more than VII. It doesn’t try to hide the fact that it’s a game. The interface takes up half the screen, there are a dozen or so unique commands (like a LucasArts point and click adventure), and there still are actual RPG elements like leveling-up and turn-based combat.

Graphically, it has that weird, tilted perspective that was in VII, but the scale is small and more tile-ish. Some of the creatures, like rats and bunnies, are depicted with an amazing economy of pixels. Despite the scale, there is a tremendous amount of stuff in the world with which to interact. Many of the puzzles involve pushing, pulling and revealing secrets.

Like previous games in the series, it’s possible to get to secrets if you know where they are in advance. A speed-runner could probably race through the game in no time. But you’ll want to take your time interacting with the NPCs.

Conversations are at the core of Ultima’s game-play. The text-parser driven dialogue is something sadly missing from most games today. It forces you to pay attention to dialogue. Lazy gamers are even given highlighted topics which to type in so you are never stuck hunting for words in normal conversations. However, since you are not given a full multiple choice list, options can be hidden from the player only to be discovered by focusing and taking good notes.

I found the best way to play this game was to reconfigure the DOSBox settings to display the game in a large window that almost fills the entire screen output=opengl, windowresolution=1360x1020, also autolock=false so you can move your mouse out of the window). Then I used the remaining space on screen to have text file open in an editor. I noted every character I met, their job, and where they were located. If they mentioned anything that seemed remotely important, I would type it in to my notes. Having a searchable file really beats hand-written scribblings and makes puzzle solving a bit more manageable.

Still, this game is old school. Don’t be ashamed to use the included clue book for help and maps. It is probably possible to put the game into an unwinnable state if you lose and important object. You only are allowed one save, so be careful. The game bugged out on me literally at the final puzzle. To win the game you need a few special objects. I was missing one of those objects so went off to get it, leaving the others in the final room. When I returned to the final room, one of the necessary items had vanished. At that moment, I was ready to go into a serious, pon farr-level nerd-rage. Fortunately, there is a debug mode still in the game and I was able to regenerate the glitched object. All was well and I had saved Britannia once again.

I remember watching my housemate play this game quite a bit back when we were in college. I don’t think he had the CD-ROM version—which included voice acting from the original cast. Luckily this GOG.com version has all the recorded elements (and none of the weird DOS set up problems). Yup, there’s nothing like hearing an aged, breathy-voiced DeForest Kelley read mediocre video game dialogue!

The past few months I have been in a Star Trek state of mind as I have been streaming episodes of The Next Generation. This game really seems to capture the essence of the shows. This is despite the opening space battle which, to me, really doesn’t feel very Trekish. Space combat pops up a few more times, but, for the most part, the game is about beaming down to worlds, exploring and solving problems. It’s broken up into nice short episodes, each with their own flavor and challenges.

As for the adventure gaming, it is pretty good but there are a couple annoying moments about halfway through the game. The Harry Mudd episode is funny but lacks purpose. The “Feathered Serpent” episode has a couple of puzzles that rely on you having taken notes early on and having a knowledge of base-3 numbers. And the final episode has a game stopping bug that will leave you wandering around with nothing to do until you are finally killed when time runs out. I can’t imagine how infuriating this game was before the age of internet walk-throughs and hints.

Just like the original show, the plots leave nothing for Sulu, Chekov, Mr. Scott or Uhura to do but sit on the bridge and mope around. It was also severely lacking in Kirk mountain-punching. Seriously, what’s TOS without some Ponfarr ritual battles?

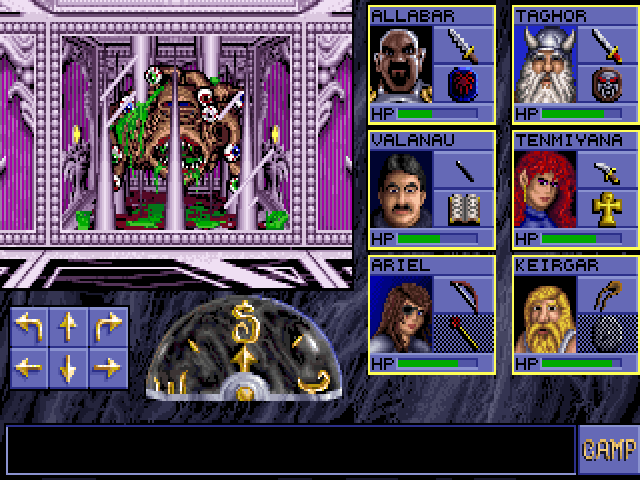

Eye of the Beholder is a real-time RPG dungeon crawl that borrows heavily from the mechanics of Dungeon Master. It’s a completely mouse-driven experience in which the objects in the environment can all be used, picked up or thrown with a click. Combat is also real-time and is generally just a mad scramble backwards as you click your various party members’ weapon hands and hope for “good rolls”.

While the fights are frantic and fun, the real meat of the game-play is exploration, mapping, and puzzle solving. I went through a dozen sheets of graph paper drawing out each floor knowing full-well I could just grab the maps from the Web (the GOG.com version even includes a complete hint book). As tedious as it might sound to modern gamers, the act of plotting out the layout is oddly satisfying. I wish it could be done in-game ála Etrian Odyssey, but, if it’s any consolation, I now have 11 floors worth of half-erased, taped together graph paper maps that are suitable for framing. Perfect for any lair!

In the end, I suppose there was a plot to follow too. Probably something about an evil wizard. dwarves and elves. None of that matters. You just need to keep going deeper and deeper. Eventually you’ll find the big boss monster and hope you have enough experience to hack it to death.

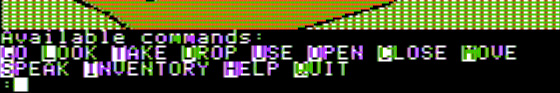

Now that my memory issues are seemingly under control, let’s take a look at my modifications to the parser. Normally, in these types of graphical adventures the player enters two words in the form of VERB OBJECT. My interface limits the number of verb choices and allows the player to enter a verb with a single keystroke.

In Applesoft you can prompt for user input in two ways. First there is INPUT A$ which will display a question mark on the screen and await user input followed by a RETURN. That user response then fills the variable A$. Similarly there is GET A$ which also displays a question mark but GET will only accept a single keypress as user input. My main problem with both of these is an aesthetic one: that darn question mark.

The solution is to write your own input routine leveraging machine code routines via PEEKs and POKEs. To do this, first I simulate a cursor by placing a flashing underscore character at the bottom of the screen.

101 VTAB 24 : HTAB 1 : CALL -868 : PRINT ":"; : FLASH : PRINT "_"; : NORMAL : GOSUB 55A lot is going on in this line. The VTAB and HTAB commands position the screen cursor at line 24 and character 1. CALL -868 is a special machine code call that clears that single line of text. Now that we have an empty line we type a colon and then a flashing underscore. The result looks like this:

This looks like a user input prompt, but at this point it does nothing. The magic happens at the subroutine which is GOSUB’d at the end of that line.

55 KEY = PEEK (49152) : IF KEY < 128 THEN 55

56 IF KEY > 224 AND KEY < 251 THEN KEY = KEY - 32 : REM UPPERCASE

57 POKE 49168,0 : BUZZ = PEEK (49200) : RETURNIn line 55 we are creating a variable KEY and assigning to it the contents of memory location 49,152 to it ($C000 for you hex-heads). Turns out location 49,152 will read the keyboard and return the ASCII value of the currently pressed key. If that value is a character then we break out of the loop and go to line 56.

Line 56 insures that, if the ASCII value of the key denotes a lowercase key, it is converted to uppercase by shifting the ASCII value. POKE 49168,0 clears the keyboard buffer so that the PEEK in 55 will work next time around and not just register the same value. Finally, that BUZZ = PEEK (49200) bit triggers a speaker click so that the player’s keystroke has and audible sound.

When we return to the main game loop we now have a variable KEY which contains an ASCII value of the key pressed. I can then branch the program based on this value. I can also test if it’s a RETURN keypress and then toggle text display. Later in my program I can concatenate keypresses into a single string value by returning to that subroutine again and again until a return press is detected. That’s how I collect the OBJECT half of the VERB OBJECT pair.

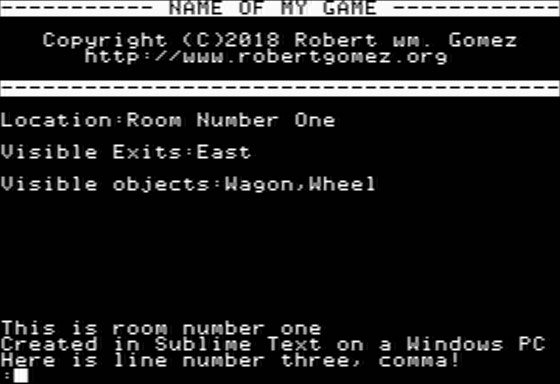

Previously I discussed the overall structure of my soon-to-be hit adventure game. Well, last night was a milestone. I managed to write an Applesoft program so epic that it overwrote the high-resolution graphics page. Compared to other programs I have seen, mine isn’t that huge. Around 250 lines isn’t that huge, right? Transylvania clocks in at 464 lines.

I think the issue is the number of arrays that I am defining. For now I think I have a fix. I have set LOMEM: 24576 at the top of my program. Supposedly, this will force the interpreter to define variables in a memory location after the hi-res pages. We shall see.

In any event, the game is back and running again. And the text screen now has some text formatting enhancements:

One of the cooler things I have implemented is this text screen. If at any prompt you hit RETURN you turn off the hi-res graphics and can see this text screen. Here will be some valuable game info included the location’s name, exits and any TAKE-able objects. The code for this is rather simple:

58 IF GM = 1 THEN GM = 0 : TEXT : RETURN

59 GM = 1 : CALL -3100 : RETURNGM is a flag which tracks where you are in graphics mode (1) or text mode (0). CALL -3100 triggers the hi-res graphics screen without erasing its contents. So exciting, right!?!

The previous post in this series explained how to get Graphics Magician images to display from Applesoft. Now, I’d like to go over the structure of the program listed in Write your Own Adventure Programs. The bulk of the program listing consists of the game data including objects, room descriptions, verbs and state flags. Most of the remaining code is comprised of a series of conditions that check how the player’s actions affect the objects in the game world.

Haunted House used a simple, two-word input parser: VERB NOUN. But I wanted this new game to simplify the number of verb choices in the same way the LucasArts adventures streamlined the interface of Sierra-style adventure games. The player will be limited to around a dozen verbs that are entered with a single keystroke.

The verb list is largely based on the options in Monkey Island. PUSH and PULL have been combined into MOVE. To move you must hit Go then enter either North, South, East, West, Up or Down. This is a little annoying, but there are only so many letters in on the keyboard and I needed that D, U and S elsewhere. Other commands require you to hit the keystroke, then type out an object NOUN and then hit Return. “Guess the verb” will no longer be an issue… welcome to 21st century “guess the noun” technology!

Each verb then get’s its own subroutine which contains the logic that triggers the various game actions (or provides a default message if nothing special happens). By assigning a number value VB to each verb, I can use the following to branch to the various subroutines: ON VB GOSUB 1000,600,800,850, ...

The game data is set in the program by assigning strings and numbers to several arrays. In Applesoft you need to declare the size of an array by dimensioning it with the DIM command. For the rooms I will set the size of the rooms array to the number of rooms RM by declaring DIM RM$(RM). Then, near the start of my program I read data into the array by using GOSUB to a loop like this:

5000 DATA "Room description 1","Room Description 2", [...]

5005 FOR I = 1 to RM : READ RM$(I) : NEXT

5010 RETURNThe DATA can be listed anywhere in the code and it’s important to make sure that there are exactly as many data strings as READ commands. Otherwise, you might get OUT OF DATA errors.

This method of declaring rooms and object will eventually make your Applesoft program very long and hard to edit. I was pretty sure that I could figure out a way to read the data in from an external text file. But more on that later.

In my previous post I wrote about the impetus behind this project. To start, I knew that my code was going to be structured around the Haunted House program in the excellent book Write your Own Adventure Programs for your Microcomputer. As I have written before, this book was crucial in my development as a programmer (I haven’t developed much beyond it). I would love to do this project in 6502 machine code and I have been trying very hard to learn 6502 assembly programming. But, although I’ve gotten a better understanding of machine code, there’s serious lack of noob-friendly practical learning exercises available out there. Sure I can draw pixels at lightning speed, but, after reading most of Assembly Lines, I still have no idea how to do a simple INPUT command or mimic an array.

So, Applesoft BASIC it is! With emulation and modern computing I have been able to develop my code on a Windows PC and then quickly run it in emulation. My workflow isn’t nearly as fancy as some other retro-programmers. I type my Applesoft in a text editor, then in AppleWin I paste the entire code listing into an emulated apple using SHIFT+INSERT. The benefit of using emulation as a development environment is that you can throttle the emulation to run hundreds of times faster (hit ScrLK) than real hardware. This makes testing small changes a breeze.

My first task was to see if I could successfully load a Graphics Magician image into a program. The program itself is a bit of a UI nightmare. Without a manual or reference card, it’s nearly impossible to know what keys do what. On top of that, the program requires that you use a joystick to move the drawing cursor on the screen. Fortunately, the manual can be found online and you can use a PC mouse as a joystick within AppleWin. I managed to crank out a couple of silly images for testing and save them to my game disk.

I then used to code provided in the manual to write a simple Applesoft program that displays the image:

1 PRINT CHR$ (4);"MAXFILES1"5 HIMEM: 32768

10 PRINT CHR$ (4);"BLOAD PICDRAWH"

20 PRINT CHR$ (4);"BLOAD ROOM1.SPC,A32768"

30 HGR

40 A = 32768:HI = INT (A / 256):LO = A - HI * 256: POKE 0,LO: POKE 1,HI50 CALL 36096In order for this code to work, you are required to copy PICDRAWH from the Graphics Magician disk to your disk. This is the machine code rendering engine that is loaded into memory at the top of this program. The MAXFILES1 DOS command apparently frees up some memory by limiting the amount of open files. This command needs to be the first one in your code, before any string assignments, etc. I think HIMEM does something similar with allocating memory locations. I have never written an Applesoft program so large that it required memory management so the purpose of these commands alludes me somewhat. As this project grows, I may have to familiarize myself with them.

You will see CHR$(4) often in Applesoft programs. CHR$() is a function that retrieves the keyboard character in assigned to the numerical value in then parenthesis. For example, PRINT CHR$(65) prints the letter A. In this case, character number four is the equivalent of keying in CTRL+D. That instructs the computer that the next PRINTed string should be executed as a DOS command rather than PRINTed to the screen.

The Graphics Magician file is ROOM1.SPC. BLOAD ROOM1.SPC,A32768 loads the drawing code into memory location 32768. That seems like a crazy random number but it is actually $8000 in hexidecimal. HGR switches to high-resolution graphics mode and then line 40 stores the memory address of the picture into a location PICDRAWH will know to look. Finally, the CALL 36096 triggers the PICDRAWH draw routines.

There’s a lot of fancy stuff going on here, but it does the job as advertised. The Graphics Magician manual also goes deeper with more code that shows how to string multiple images into slide shows and how to overlay objects over backgrounds. More on that when I get to my object code. For now, this proof-of-concept was enough to get a simple working prototype up and running.